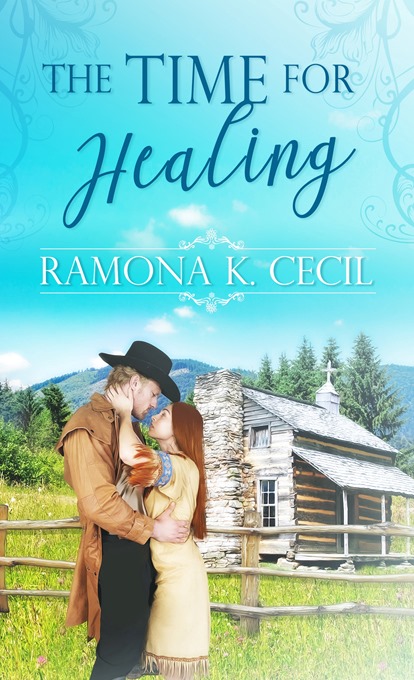

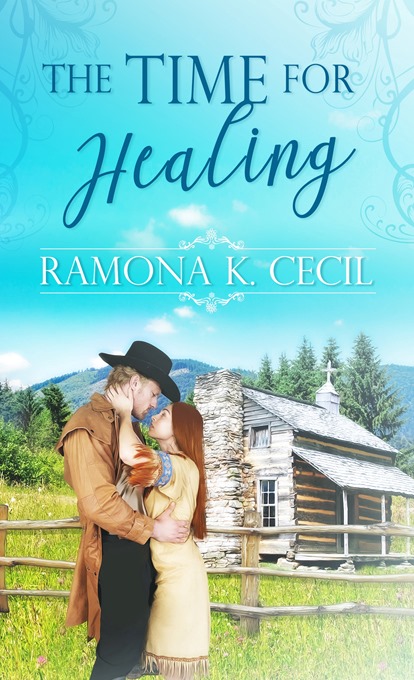

Ginny Red Fawn McLain, a Shawnee medicine woman, is thrust back into the world of her birth family twelve years after her abduction. While she eschews the Christianity preached by her birth uncle who found her, Ginny’s heart refuses to shun his friend and fellow Christian minister, Jeremiah Dunbar. Jeremiah is immediately smitten with his friend’s long-lost niece. But unless Ginny Red Fawn joins Christ’s fold—something she adamantly resists—any future with the woman he loves is impossible.

Ginny Red Fawn McLain, a Shawnee medicine woman, is thrust back into the world of her birth family twelve years after her abduction. While she eschews the Christianity preached by her birth uncle who found her, Ginny’s heart refuses to shun his friend and fellow Christian minister, Jeremiah Dunbar. Jeremiah is immediately smitten with his friend’s long-lost niece. But unless Ginny Red Fawn joins Christ’s fold—something she adamantly resists—any future with the woman he loves is impossible.

Please welcome to my website and blog today–Ramona Cecil, award-winning author of historical Christian fiction. I’ve known Ramona for about 12 years through American Christian Fiction Writers. Her books are wonderful, her characters unforgettable, and her plot lines resonate with the heart. Welcome, Ramona. Thanks for dropping by. Share with the readers about your upcoming release, “The Time For Healing.” ~ Connie

The Time for Healing – Releases August 7th with Pelican Book Group

Hi! I’m Ramona K. Cecil and I’d like to talk about my new historical romance novel, The Time for Healing. I love history, especially the history of my Hoosier state and many of my stories are set there. The Time for Healing was inspired by the Pigeon Roost Massacre, a tragic event that happened in 1812 in southern Indiana. There, on a serene September afternoon, the unsuspecting frontier settlement of Pigeon Roost was set upon by a contingent of hostile, Shawnee warriors. Twenty-three settlers were killed and it was said that two children were taken captive. The story was told, though also refuted, that many years later one of these children—a little girl—was found by her missionary uncle, living among the Shawnee along the Kankakee River. In The Time for Healing, I re-imagined the compelling story of the little girl taken captive by the Shawnee. I thought for fun today I’d share the unpublished prologue to the story followed by an excerpt from opening chapter of the book.

Hi! I’m Ramona K. Cecil and I’d like to talk about my new historical romance novel, The Time for Healing. I love history, especially the history of my Hoosier state and many of my stories are set there. The Time for Healing was inspired by the Pigeon Roost Massacre, a tragic event that happened in 1812 in southern Indiana. There, on a serene September afternoon, the unsuspecting frontier settlement of Pigeon Roost was set upon by a contingent of hostile, Shawnee warriors. Twenty-three settlers were killed and it was said that two children were taken captive. The story was told, though also refuted, that many years later one of these children—a little girl—was found by her missionary uncle, living among the Shawnee along the Kankakee River. In The Time for Healing, I re-imagined the compelling story of the little girl taken captive by the Shawnee. I thought for fun today I’d share the unpublished prologue to the story followed by an excerpt from opening chapter of the book.

Scott County Indiana, September 3, 1812

“It’s time for you to feed the chickens and bring in the eggs, Ginny.”

Ginny blew out a long breath and dropped her rag and cornhusk doll to the floor. It was a good baby. No matter what she did with it, it never cried. She walked, but not too fast, across the room to the fireplace where Ma held out a bucket half full of shelled corn while bouncing Ginny’s squalling baby brother in her other arm. “Maybe if the house is quiet, I can finally get Joe to sleep.”

“Yes, Ma.” Ginny wanted to say that it was Joe making all the noise, not her. But the way Ma’s mouth was all puckered up liked she’d bit into a green persimmon told Ginny she was in no mood for sass.

Not wanting to risk a switching, Ginny kept quiet and took the bucket with both hands. The rope handle scratched her palms while the bucket’s weight pulled hard on her arms, making them burn. She wouldn’t complain. Feeding the chickens gave her a good excuse to get out of the house and away from Joe’s crying that made her ears hurt.

At least today she wouldn’t have to shell the corn. When she pushed the grain away from the soft red cobs, the rough, dry kernels always dug into the heels her hands, making them sting.

Before baby Joe came she had less work to do and more time to play. Ma seemed to know that Ginny wished Joe hadn’t come because she’d say things like “You’re a big sister now, all of six years old. ’Fore you know it, you’ll be growed.” As if that would make her like her brother better. It didn’t. Maybe she’d like him better when he got old enough to play with her, but right now she’d rather have her doll.

Ma followed Ginny to the cabin’s open door. “And don’t rip your dress or get it dirty” she said over Joe’s cries. “Uncle Zeb and Aunt Ruth are comin’ for supper.”

“Yes, Ma.” Nodding, Ginny lugged the bucket down the two stone steps and headed toward the pine trees where the chickens would roost for the night. She liked this time before supper when the sunshine poked through the pine grove around their cabin. It looked like melted butter the way it poured through the trees and settled in yellow puddles in the dirt. She liked the way things smelled this time of day, too. The pine needles smelled stronger, and she could even smell the creek water, fresh and cool beyond the trees where bullfrogs had already started their croaking. They sounded like they had a bad case of the hiccups, only deeper. She paid attention to things like that. Aunt Ruth said that was why Ginny would do well when she went to school.

“Chick, chick, chick,” she called.

Their wings flapping, the chickens appeared from the brambles and the shadows behind the trees. Ginny liked the colors of the chickens, some black and white speckled, some all snowy white, and some a reddish brown color that almost matched the color of Ginny’s hair. Their eggs were different colors, too. Some white and some brown. She was eager to see how many she might find in the thicket where the chickens had made their nests against the trunk of an old fallen tree. She’d have to be careful to get all the eggs and not leave any behind for the raccoons and other varmints to steal.

She grinned down at the plump birds as they strutted and clucked and pecked at the dirt. “Puck, puck, puck, puckaw!” Cocking their red-crowned heads sideways, they looked up at her with eyes like big black peppercorns and clucked louder, begging for the corn.

Ginny grabbed a handful of kernels from the bucket and scattered them over a patch of bare ground, too shaded for grass to grow. While the chickens pecked at the corn, Ginny jabbed the air with her finger, practicing her counting like Aunt Ruth had taught her.

“One, two, three. Stand still so I can count you. Four, five, six. Six hens and one, two roosters.” She especially liked the roosters. They stood taller than the hens and puffed out their big chests when they walked. The combs on their heads and the dangly things under their chins were bigger and brighter red than the ones on the hens, and they had sharp toenails on the backs of their legs that could scratch her if she wasn’t careful. But Ginny loved their brightly colored tail feathers that curled behind them and looked like little rainbows in the sunlight.

“That makes eight,” she said, proud of herself as she finished counting. At supper, she would show Aunt Ruth and Uncle Zeb how well she could count. Aunt Ruth would be proud of her, too. Ginny was glad Aunt Ruth was the school teacher. Even if Ma needed Ginny to stay home and help with chores and not go to school for another year or two, she would not get behind in her learning.

An owl hooted. It sounded close.

Ginny looked up into the pine boughs above her. She’d never heard an owl call while it was still this light. And Ginny paid attention to these things.

Another owl hooted, and then another. But the sound didn’t come from up in the trees. It came from near the ground over by the creek. Why would owls walk when they could fly? Pa said they liked to roost high in the trees and look down on everything.

Pa.

Pa should have been back from driving their cow, Sadie, home from the meadow where she liked to graze. The tallest pine tree’s shadow stretched across the yard and bent up against the cabin. Pa was always home before the shadow touched the cabin.

A scream came from inside the cabin, chilling Ginny like the time last winter when she fell into the creek. The sound froze her in place, and the bucket’s rope handle slipped from her fingers. Somehow she knew it was Ma that had screamed, but it didn’t sound like Ma. Joe wailed, but then he stopped right in the middle of his crying and everything got quiet. Joe had never stopped crying all of a sudden like that.

Ginny looked down where she’d dropped the bucket, spilling the corn in a yellow heap. She reached down to pick up the bucket, but someone grabbed her arm. She looked up and saw a man with red lines painted across his face standing over her. He didn’t have much hair, just a little in the back, and a large gray and white feather dangled from it. His chest was bare and large rings hung from his ears and nose.

She tried to scream like Ma had, but nothing came out.

The Time for Healing opens up twelve years later along southern Missouri’s White River. The following is an excerpt from the first chapter:

Shawnee village, southern Missouri, 1824:

“Life will change for you soon, Daughter.” At her mother’s quiet words, anger rumbled through Red Fawn like the low howl of the autumn wind outside their wigwam. She knelt and tugged the shaggy buffalo robe closer under her mother’s swollen chin. Their tribe had moved twice since they buried her father where the Pigeon Creek flows into Spelewathiipi, the big river the white man called Ohio. She hated the thought of moving again before the time of the Spring Bread Dance. And she hated the whites who would force that move.

“Life will change for all of us when the white man makes new laws that will force us to move west again.” Would Mother even survive another move? Red Fawn’s heart quaked at the thought.

“No, Daughter.” Mother shook her head as she rose onto one elbow and coughed. Her raven braids streaked with silver shook with her convulsive movements. Red Fawn snatched a scrap of cloth from a nearby basket and handed it to her mother, who pressed it to her mouth. Despite Red Fawn’s efforts, her mother grew weaker. When her coughing had subsided, Mother grasped Red Fawn’s hand. The comparison of her own freckled skin against the smooth brown hue of Mother’s jarred Red Fawn anew, reminding her that she hadn’t been born a Shawnee.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

I hope you get to check out The Time for Healing. Here are the links for ordering your copy.

Amazon: https://www.amazon.com/Time-Healing-Ramona-K-Cecil/dp/1522302328/ref=sr_1_1?crid=1S3QFJVY2ZESB&dchild=1&keywords=the+time+for+healing+ramona+k.+cecil&qid=1593278046&s=books&sprefix=The+Time+for+%2Cstripbooks%2C152&sr=1-1

Barnes&Noble: https://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/the-time-for-healing-ramona-k-cecil/1134332259?ean=9781522302322

Thrift Books: https://www.thriftbooks.com/w/the-time-for-healing_ramona-k-cecil/24295657/#isbn=1522302328

Book Despository: https://www.bookdepository.com/author/Ramona-K-Cecil

Leave a comment for a chance to win an e-copy of the book!

Ramona K. Cecil is a wife, mother, grandmother, freelance poet, and award-winning inspirational romance writer. Now empty-nesters, she and her husband make their home in Indiana. A member of American Christian Fiction Writers and American Christian Fiction Writers Indiana Chapter, her work has won awards in a number of inspirational writing contests. She’s the author of thirteen novels and novellas. Over eighty of her inspirational verses have been published on a wide array of items for the Christian gift market. Through her speaking ministry, she enjoys encouraging aspiring writers by sharing her story of how she became a published author. When not writing, her hobbies include reading, gardening, and visiting places of historical interest.

Thanks for being our guest blogger today, Ramona.

Folks, don’t forget to leave a comment for a chance to win a free e-book!

In High Cotton

In High Cotton Ane Mulligan has been a voracious reader ever since her mom instilled within her a love of reading at age three, escaping into worlds otherwise unknown. But when Ane saw PETER PAN on stage, she was struck with a fever from which she never recovered—stage fever. She submerged herself in drama through high school and college. One day, her two loves collided, and a bestselling, award-winning novelist emerged. She lives in Sugar Hill, GA, with her artist husband and a rascally Rottweiler. Find Ane on her website, Amazon Author page, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Pinterest and The Write Conversation.

Ane Mulligan has been a voracious reader ever since her mom instilled within her a love of reading at age three, escaping into worlds otherwise unknown. But when Ane saw PETER PAN on stage, she was struck with a fever from which she never recovered—stage fever. She submerged herself in drama through high school and college. One day, her two loves collided, and a bestselling, award-winning novelist emerged. She lives in Sugar Hill, GA, with her artist husband and a rascally Rottweiler. Find Ane on her website, Amazon Author page, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Pinterest and The Write Conversation.

Ginny Red Fawn McLain, a Shawnee medicine woman, is thrust back into the world of her birth family twelve years after her abduction. While she eschews the Christianity preached by her birth uncle who found her, Ginny’s heart refuses to shun his friend and fellow Christian minister, Jeremiah Dunbar. Jeremiah is immediately smitten with his friend’s long-lost niece. But unless Ginny Red Fawn joins Christ’s fold—something she adamantly resists—any future with the woman he loves is impossible.

Ginny Red Fawn McLain, a Shawnee medicine woman, is thrust back into the world of her birth family twelve years after her abduction. While she eschews the Christianity preached by her birth uncle who found her, Ginny’s heart refuses to shun his friend and fellow Christian minister, Jeremiah Dunbar. Jeremiah is immediately smitten with his friend’s long-lost niece. But unless Ginny Red Fawn joins Christ’s fold—something she adamantly resists—any future with the woman he loves is impossible. Hi! I’m Ramona K. Cecil and I’d like to talk about my new historical romance novel, The Time for Healing. I love history, especially the history of my Hoosier state and many of my stories are set there. The Time for Healing was inspired by the Pigeon Roost Massacre, a tragic event that happened in 1812 in southern Indiana. There, on a serene September afternoon, the unsuspecting frontier settlement of Pigeon Roost was set upon by a contingent of hostile, Shawnee warriors. Twenty-three settlers were killed and it was said that two children were taken captive. The story was told, though also refuted, that many years later one of these children—a little girl—was found by her missionary uncle, living among the Shawnee along the Kankakee River. In The Time for Healing, I re-imagined the compelling story of the little girl taken captive by the Shawnee. I thought for fun today I’d share the unpublished prologue to the story followed by an excerpt from opening chapter of the book.

Hi! I’m Ramona K. Cecil and I’d like to talk about my new historical romance novel, The Time for Healing. I love history, especially the history of my Hoosier state and many of my stories are set there. The Time for Healing was inspired by the Pigeon Roost Massacre, a tragic event that happened in 1812 in southern Indiana. There, on a serene September afternoon, the unsuspecting frontier settlement of Pigeon Roost was set upon by a contingent of hostile, Shawnee warriors. Twenty-three settlers were killed and it was said that two children were taken captive. The story was told, though also refuted, that many years later one of these children—a little girl—was found by her missionary uncle, living among the Shawnee along the Kankakee River. In The Time for Healing, I re-imagined the compelling story of the little girl taken captive by the Shawnee. I thought for fun today I’d share the unpublished prologue to the story followed by an excerpt from opening chapter of the book. In my current work-in-progress, there is a character who is disliked by the other characters. Her name is Josephine Templeton. Before the readers meet Josephine, the other characters mention her in dialogue. They hint that Josephine is not a nice person. When the reader does get to meet her, their expectations are fulfilled–at first. Josephine is a harsh, critical, judgmental person. Because of her position, she has the ability to make those who work under her miserable. At this point the reader is thinking, “Wow, what a witch! I’d hate to work for her!”

In my current work-in-progress, there is a character who is disliked by the other characters. Her name is Josephine Templeton. Before the readers meet Josephine, the other characters mention her in dialogue. They hint that Josephine is not a nice person. When the reader does get to meet her, their expectations are fulfilled–at first. Josephine is a harsh, critical, judgmental person. Because of her position, she has the ability to make those who work under her miserable. At this point the reader is thinking, “Wow, what a witch! I’d hate to work for her!” Characters who are assigned lines of dialogue, but have not had a benefit of any description, are called “talking heads.” We can hear them but we don’t know what they look like. If a character doesn’t play a major role in the story, or even if he is what I call a “wallpaper character”–meaning he only appears in one or two scenes and is there for the protagonist to exchange dialogue to move the story forward–he still has a face, or perhaps a funny quirk. The reader doesn’t need to know his life history, his favorite color, or his shoe size, but let the reader see his wispy gray hair that sticks out in all directions, or the ink stains on his shirt. Maybe he has a gap between his teeth, or maybe his speech pattern is odd. Give the reader a quick glimpse of even the minor characters before your protagonist moves on.

Characters who are assigned lines of dialogue, but have not had a benefit of any description, are called “talking heads.” We can hear them but we don’t know what they look like. If a character doesn’t play a major role in the story, or even if he is what I call a “wallpaper character”–meaning he only appears in one or two scenes and is there for the protagonist to exchange dialogue to move the story forward–he still has a face, or perhaps a funny quirk. The reader doesn’t need to know his life history, his favorite color, or his shoe size, but let the reader see his wispy gray hair that sticks out in all directions, or the ink stains on his shirt. Maybe he has a gap between his teeth, or maybe his speech pattern is odd. Give the reader a quick glimpse of even the minor characters before your protagonist moves on. Sensory details pull the reader into the story. Let the reader smell the fresh loaves of bread cooling on the table, or the fragrance of clover and summer grasses in a meadow. The sound of a sawmill, a cattle ranch, a busy street, or a thunderstorm moving in, or the grating sound of a character’s nasal-quality voice can help paint an image for the reader. Let the reader feel the thorny vines snagging at the character’s hands and arms when she picks blackberries, or taste the sweet blackberry juice on her tongue when the character pops a few berries into her mouth. Sensory details put the reader into the character’s head, and description creates a story world into which your reader can step.

Sensory details pull the reader into the story. Let the reader smell the fresh loaves of bread cooling on the table, or the fragrance of clover and summer grasses in a meadow. The sound of a sawmill, a cattle ranch, a busy street, or a thunderstorm moving in, or the grating sound of a character’s nasal-quality voice can help paint an image for the reader. Let the reader feel the thorny vines snagging at the character’s hands and arms when she picks blackberries, or taste the sweet blackberry juice on her tongue when the character pops a few berries into her mouth. Sensory details put the reader into the character’s head, and description creates a story world into which your reader can step. Whether your scene takes place in a plush, ornate room, or a pitiful shack, the reader would like to see his surroundings. An historical cabin is a very different setting from modern-day home. A rustic prairie town won’t sound or smell the same as a bustling city. A farm definitely won’t sound or smell the same as a high-end penthouse. Allowing your reader to step into the scene and experience the setting around her pulls her deeper into the story. The reader is now part in the story because she is standing in the middle of it.

Whether your scene takes place in a plush, ornate room, or a pitiful shack, the reader would like to see his surroundings. An historical cabin is a very different setting from modern-day home. A rustic prairie town won’t sound or smell the same as a bustling city. A farm definitely won’t sound or smell the same as a high-end penthouse. Allowing your reader to step into the scene and experience the setting around her pulls her deeper into the story. The reader is now part in the story because she is standing in the middle of it. This is NOT to imply you should drop in a block of descriptive narrative, painting a picture of the setting. Don’t stop the forward progression of the story to use half of a page telling the reader every detail of the platform on which the actors are playing. Instead, weave the setting details into the character’s POV. How does he react to the noise of the city? Does she cringe at the sight and smell of animal droppings around the barnyard? Does envy strike a strident chord when the character runs her fingers over the silk tapestry-covered furniture? Is your character fascinated by unusual wildflowers, or trees? Perhaps he reaches to pluck a flower, only to have thorny vines scratch his hand.

This is NOT to imply you should drop in a block of descriptive narrative, painting a picture of the setting. Don’t stop the forward progression of the story to use half of a page telling the reader every detail of the platform on which the actors are playing. Instead, weave the setting details into the character’s POV. How does he react to the noise of the city? Does she cringe at the sight and smell of animal droppings around the barnyard? Does envy strike a strident chord when the character runs her fingers over the silk tapestry-covered furniture? Is your character fascinated by unusual wildflowers, or trees? Perhaps he reaches to pluck a flower, only to have thorny vines scratch his hand. When writing in Deep POV, I go a step further. My POV character, James, has lived in this area of the country for all 74 of his years. For him to use perfect grammar would be out of character. Likewise, for him to think with perfect grammar would be unnatural. When I am writing in James’s POV, his narrative reflects the way he speaks. When he observes another person shaking his head in disagreement, James thinks: He waggled his head like he were tryin’ to shake a doodlebug out o’ his ear. This is in the narrative–James’s thoughts, not his dialogue. If I were to re-write this narrative to read: He shook his head in vehement disagreement, it would sound like a narrator was standing backstage with a microphone, telling the reader what James was thinking. It certainly would not sound like James, and I would much rather the reader would see what James is thinking.

When writing in Deep POV, I go a step further. My POV character, James, has lived in this area of the country for all 74 of his years. For him to use perfect grammar would be out of character. Likewise, for him to think with perfect grammar would be unnatural. When I am writing in James’s POV, his narrative reflects the way he speaks. When he observes another person shaking his head in disagreement, James thinks: He waggled his head like he were tryin’ to shake a doodlebug out o’ his ear. This is in the narrative–James’s thoughts, not his dialogue. If I were to re-write this narrative to read: He shook his head in vehement disagreement, it would sound like a narrator was standing backstage with a microphone, telling the reader what James was thinking. It certainly would not sound like James, and I would much rather the reader would see what James is thinking. The story I am currently working on features a young man and an old man as two of the characters. The young man is searching, seeking for purpose and acceptance. Having grown up in the shadow of an older brother who always succeeded at everything he did, this character never managed to win his father’s affection or approval. How often do we encounter someone who is either estranged from a parent, or never truly knew the love of a parent? More often than we might think. When readers identify with your characters’ circumstances or background, they connect with that character emotionally. They root for them, they want to see that character rise above the issues from his past. Isn’t that what we do with each other? If a friend is dealing with a hurtful situation, we pray for them, we try to encourage them. That’s what we want our readers to do with our characters.

The story I am currently working on features a young man and an old man as two of the characters. The young man is searching, seeking for purpose and acceptance. Having grown up in the shadow of an older brother who always succeeded at everything he did, this character never managed to win his father’s affection or approval. How often do we encounter someone who is either estranged from a parent, or never truly knew the love of a parent? More often than we might think. When readers identify with your characters’ circumstances or background, they connect with that character emotionally. They root for them, they want to see that character rise above the issues from his past. Isn’t that what we do with each other? If a friend is dealing with a hurtful situation, we pray for them, we try to encourage them. That’s what we want our readers to do with our characters. This young character of mine, in the course of his struggles, encounters the old man. At first the young man is viewed as an adversary. The old man and his granddaughter believe this guy wants to cheat them out of their land. During the course of the story, however, the older man’s insight discerns the need in the young man’s life. His years of walking with God have given him perception, and he employs gentle patience and faith in dealing with the young man.

This young character of mine, in the course of his struggles, encounters the old man. At first the young man is viewed as an adversary. The old man and his granddaughter believe this guy wants to cheat them out of their land. During the course of the story, however, the older man’s insight discerns the need in the young man’s life. His years of walking with God have given him perception, and he employs gentle patience and faith in dealing with the young man.

Our characters will sometimes attempt to hide their true feelings from the other characters in the story, but they can’t hide them from the reader. Often, one or two of the plot threads involve a main character concealing his past, or the heroine struggling with trust issues because of an earlier betrayal. Perhaps a character never felt that he measured up when compared with a sibling, or constantly failed at everything he ever tried to do. Maybe one of your characters has a checkered past and he is seeking a fresh start. Even if the other characters in the story aren’t aware of the hero/heroine’s struggles, the reader must be able to identify and commiserate with them. Otherwise, the reader has no reason to keep turning pages.

Our characters will sometimes attempt to hide their true feelings from the other characters in the story, but they can’t hide them from the reader. Often, one or two of the plot threads involve a main character concealing his past, or the heroine struggling with trust issues because of an earlier betrayal. Perhaps a character never felt that he measured up when compared with a sibling, or constantly failed at everything he ever tried to do. Maybe one of your characters has a checkered past and he is seeking a fresh start. Even if the other characters in the story aren’t aware of the hero/heroine’s struggles, the reader must be able to identify and commiserate with them. Otherwise, the reader has no reason to keep turning pages. For my current project, I’m trying to find out if there were any laws or ordinances that protected cemeteries from being disturbed (think dug up, moved, or built upon) in the late 19th century. In 2018, the very thought of erecting a building on top of graves is absurd, but a power-hungry character in 1886 might not think the same way. After all, there must have been a time when it became necessary to pass such laws. So. . . when was that?

For my current project, I’m trying to find out if there were any laws or ordinances that protected cemeteries from being disturbed (think dug up, moved, or built upon) in the late 19th century. In 2018, the very thought of erecting a building on top of graves is absurd, but a power-hungry character in 1886 might not think the same way. After all, there must have been a time when it became necessary to pass such laws. So. . . when was that?